Imagine weather so frightful, every drop of rain was determined to bring you down to the cold, hard asphalt. A world where crying babies sit idly in cars, crummy palms to windows, waiting for mommies and daddies to return from running errands. Cashiers so concerned with criminals—probably young criminals who couldn’t get jobs—they don’t even notice their coworkers flipping off crippled old people signaling for help. Imagine explosions, the air sullied with toxic fumes…

Imagine weather so frightful, every drop of rain was determined to bring you down to the cold, hard asphalt. A world where crying babies sit idly in cars, crummy palms to windows, waiting for mommies and daddies to return from running errands. Cashiers so concerned with criminals—probably young criminals who couldn’t get jobs—they don’t even notice their coworkers flipping off crippled old people signaling for help. Imagine explosions, the air sullied with toxic fumes…

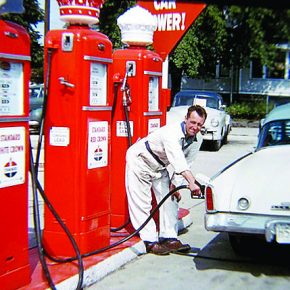

This is a (slightly exaggerated) picture of what life would look like if Oregonians had permission to pump their own gas, extracted from the verbiage used by our very own legislature. Except for rural Oregonians, between 6 p.m. and 6 a.m.

To spare our running-on-empty rural drivers from finding an abandoned pump in the wee hours, the State Fire Marshal declared this 12-hour-a-day exception in areas with populations of less than 40,000. Surprisingly, not too many rural attendants found graveyard gas pumping appetizing. Why? I don’t know. Who doesn’t love pulling all-nighters of breathing gasoline and repetitive motions?

Where It All Started

Since pairing up with New Jersey—or the Dirty Jerz as we Eastern-conceived call it—in 1951 and enacting a self-service ban at retail gasoline stations, Oregon’s Legislative Assembly issued 17 declarations that framed the task of pumping gas as seriously risky business, alongside arguing that legally requiring service attendants is a major job-generator. The declarations go so far as to fault Oregon’s “uniquely adverse weather,” which wreaks havoc via super slipperiness and reduced visibility for customers and cashiers in the face of everyday gas station mischief… Gosh, all that gas station mischief, you know?

On all of my out-of-state stops to top off the tank, I never once felt so imperiled. The lengths of such legislative scare tactics are a baffling kind of comical, given that all other 48 states generally manage safe self-service environments, even through a hard rain. If the threats posed by our Legislative Assembly retained any merit, couldn’t we expect some statewide enforcement of precautionary measures?

Basic Training, Emphasis on the Basic

For Chazz Loftis, local ARCO station attendant at NW 3rd Street, training came in the form of a small handbook to quickly flip through before reporting to the pump. I’m not pointing any fingers at his superiors for brevity of procedure, because like Loftis, I understand how pumping gas is for the most part pretty simple.

Trainings are only slightly more extensive—between one and two hours—for employees under Mitch Dong, owner of the Shell convenience store on SW 4th Street. Dong’s biggest concern is teaching attendants to make sure customer payments clear before leaving their pumps.

Fire, Fumes, and ‘Full’ Service

As far as I can tell, fire hazards are no focal point during training, as you’d expect after reading our Legislature’s declarations. Probably because ways of preventing flames are common knowledge—engines off and butts out. Our local attendants aren’t ordained firefighters, nor mechanics.

It seems “full-service,” which ensures customers added options like window squeegees and oil checks, isn’t a blanket rule for Oregon stations. Neither the Shell or ARCO I’ve contacted are required to perform maintenance checks, a facet backed by the assembly as it claims self-service results in “neglect of maintenance, endangering both the customer and other motorists and resulting in unnecessary and costly repairs.” I don’t know about you, but I’ve never been offered an oil check, nor been saved from any imminent vehicular catastrophe at the pump.

During our 11 billion annual fill-ups, only around 5,000 station fires are responded to, most of which are vehicle fires, sourced at cracked, leaking O-rings gone undetected—if not prevented by the “full-service” you’re not guaranteed. The odds of encountering a pump fire are slim, most obviously alongside the likelihood of being struck by lightning. On average, two gas pump-related deaths and 48 injuries occur annually, while lightning strikes kill 51 victims and leave around 297 injured per year, making death by lightning about 25 times more likely.

I don’t disregard the intrinsic toxicity of gasoline. Drunk or ignited, gasoline can be lethal, but it poses little threat when handled at retail gasoline stations, traveling, as Dong says, straight from pump to tank. The average consumer is exposed mainly to toxic fumes, which, according to our heroic Assembly, “represents a health hazard to customers” so should be “limited to as few individuals as possible.”

The inequity bared by this logic is reprehensible, as it indicates the dire consequences of breathing in gasoline fumes and then proposes we concentrate exposure to a certain job type, for the sake of the majority’s safety and convenience.

If the law’s going to lay it all down on our attendants, why aren’t they given medical check-ups? Why aren’t they all wearing gas masks? For the same reason most of us don’t slip on the hazmat suit for a stroll down the street or when fetching the car from the shop. Everyday exposure to the general public renders little concern, yet it’s worth considering what happens when exposure becomes unleveled.

Save the Young and Vulnerable!

The declarations rally for the health and convenience of our most young or vulnerable populations: “persons with disabilities, elderly persons, small children and those susceptible to respiratory diseases.” Calling on the federal Americans with Disabilities Act, which requires equal access to all consumers, the Assembly finds self-service retailers guilty of neglect in failing to provide aid to the less able-bodied. I don’t know, nor have I ever heard of, any self-service station that would purposefully ignore a customer, disabled or not. In these cases, we can clearly fault poor procedure, work ethic, or straight-up ignorance.

Taking it straight to utero, the Assembly declares exposure is especially hazardous for pregnant customers. I wondered, then, what protocol was for pregnant attendants. Neither Dong or Loftis seemed to know of any clear directives given said circumstance, however Dong assumed a pregnant employee wouldn’t need to leave the job, unless doctor-ordered.

The legislature’s declared finale, of course, calls on small children, whom if “left unattended when customers leave to make payments… creates a dangerous situation.” There’s your grand-slam no-sh*t moment. Who leaves small children in cars these days? Just take them with you.

The Job Debate

Loftis admits that constantly breathing in gasoline is probably taking some kind of toll on his overall health, but he’s not too concerned. The gasoline service industry is probably more of a placeholder than a permanent position for most. Dong marks his employee stay-rate between a couple weeks to 10 years, the record held by his veteran assistants, who likely take pleasure in the ease of the trade.

The monotonous simplicity of such a job can be a fast track to taxing boredom. And having to encounter all permutations of humanity can only add to agitation, as many attendants are subject to stigma and maltreatment. Loftis is well-treated “half of the time,” and who knows how attendants fare beyond the bounds of our happy little borough.

The argument that the ban creates jobs—around 98,000 jobs to be exact—while providing “sustained reduction in fuel prices” is strongest in sway, yet not so sturdy. Prices depend on multiple variables such as state taxes and regulations, and distance to pipelines and refineries. Basic economy suggests the added cost of labor forces gas prices up. Some economists estimate Oregonians spend an extra three to five cents per gallon.

As gasoline is a generic and visibly priced product, economists say the disproportionate mix of (most) single-service and (some) full-service stations—a.k.a. those that offer oil checks and maintenance—in Oregon influences competition to stay in the higher range, as single-servers are able to circulate costs on par with full-service competitors. Any excess profit expected to be gained by owners if attendants were eliminated would likely be lost to competition, kept in the pocket of the consumer.

Leftover funds from eliminated attendants might be utilized for better jobs and better technology, which snuffs the declaration claiming, “appropriate safety standards often are unenforceable at retail self-service stations in other states because cashiers are often unable to maintain a clear view of and give undivided attention [to customers].” Here we see how outdated the mandate really is. High-tech 24-hour surveillance sounds much better than forcing graveyard gas shifts on employees.

Away with Arbitrary Law

I think it’s safe to say the legislature dug its own grave with all they’ve declared, gunning for the “young people” they claim self-service leaves stranded and unemployed. Oregon was last reported with the 12th highest unemployment rate in the US, plus these are the same young people they subject to the majority of exposure, a contradiction leveling the injustices they declare self-service stations impose on vulnerable populations. The only “public welfare” promoted, or form of protection the prohibition provides, is from our own stupidity, which probably varies just as much as the person pumping for you.

I know Oregonians are extremely attached to their cushy driver-side seats, warm and out of rain’s reach, but all we’re doing is planting bodies in unnecessary middle ground and fostering fear and incompetence. As of now, any pursuit in learning to pump will land Oregonians a $500 fine. I say, the restriction is plain arbitrary, given the simple biomechanics required—or if pumping gas really is so hazardous, the people doing it deserve a far fairer package.

By Stevie Beisswanger

Do you have a story for The Advocate? Email editor@corvallisadvocate.com